Venus' Volcanic Surface

Venus is one of the easiest objects to spot in the night sky. Its thick clouds reflect most of the sunlight that hits the planet, making it shine as the third brightest object after the Sun and the Moon. But despite being so visible, Venus remains a very secretive world. Its clouds completely block its surface from view. Even with a telescope or from a passing spaceship, you'd only see the thick cloud cover. The only way to uncover what lurks below Venus' clouds is by travelling through them to the surface, or using radar technology to see through them. Rather fortunately, this is exactly what some brainy space scientists have done.

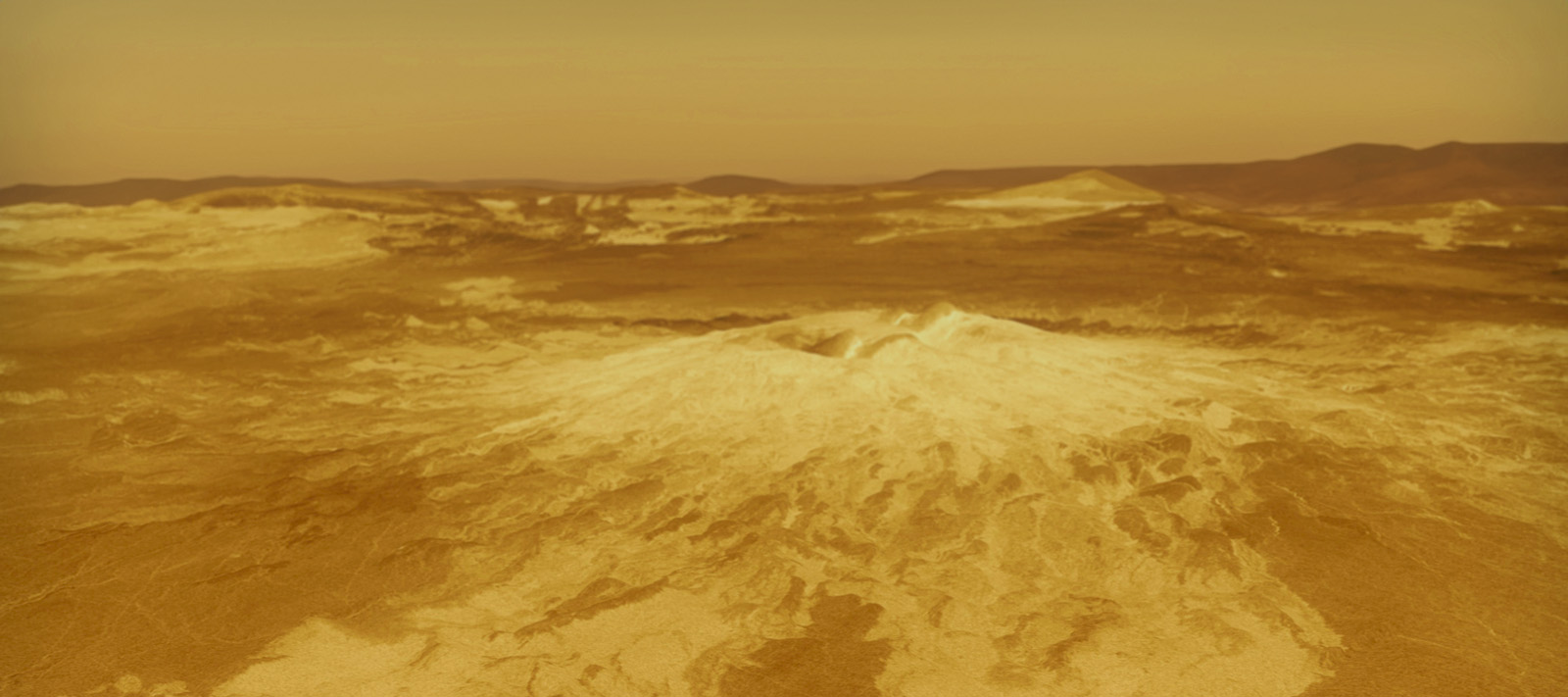

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Soviet Union's Venera landers successfully touched down on the surface of Venus, and in the 1990s, NASA's Magellan mission used radar to map nearly the entire surface of Venus. What they revealed is a totally hostile environment, where temperatures can melt lead, surface pressure is like being almost a kilometre underwater, and volcanoes dominate the landscape. It's no wonder that Venus likes to keep its surface hidden!

Landing on Venus today would feel like stepping into an oven - an oven that’s also trying to crush you. The surface temperature reaches a scorching 471°C (880°F), and the atmospheric pressure is 90 times greater than on Earth. It’s so hot that parts of Venus’ surface might even glow faintly through the clouds!

But Venus wasn’t always this way. Billions of years ago, Venus might have looked more like Earth, with rivers, lakes, and even oceans of water. With a cooler climate, Venus could have supported and may have even been habitable. However, as the Sun grew hotter, Venus’ water evaporated, creating a thick, dense atmosphere that trapped more and more heat. This led to a runaway greenhouse effect, turning Venus’ surface into the volcanic, dry landscape it is today.

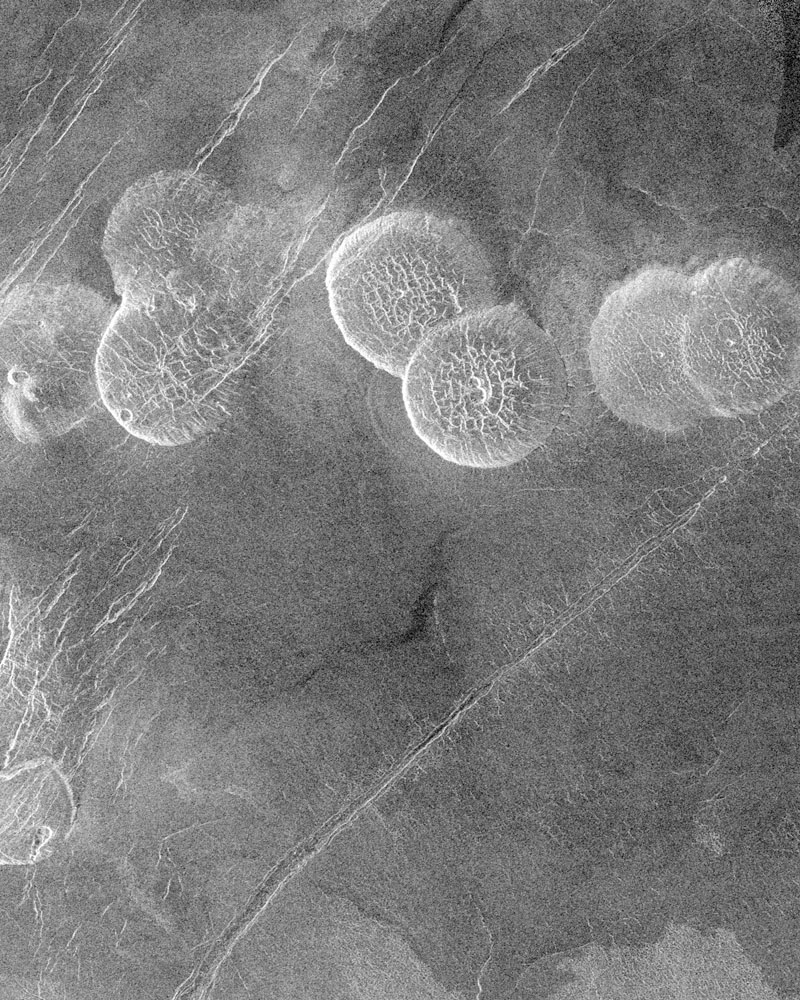

Venus doesn't just hold the award for hottest planet in the Solar System. It also has the title of most volcanic planet in the Solar System. Its surface is home to over 160 massive volcanoes, each more than 100 kilometers across, and thousands of smaller ones. Some of these volcanoes are familiar in shape, while others - like the pancake domes - are unlike anything on Earth. These pancake domes are flattened, wide volcanoes, likely caused by the slow eruption likely caused by the slow eruption of thick, hot lava, much like treacle, that spreads slowly across the surface, forming a broad, round shape—just like a pancake. Mmmmmmm.... treacle and pancakes.

Unlike Earth, Venus doesn’t have tectonic plates - the huge pieces of Earth's outer shell that float on the planet's mantle (the layer of molten rock beneath the surface). On Earth, these plates move around, shifting continents and causing earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Venus, on the other hand, is shaped almost entirely by volcanic activity. Venus was once extremely geologically active, but scientists don't know how active it is today, or even if it is still active. Many strongly suspect that it is, and recent analysis of images taken by the Magellan spacecraft in the 1990s suggest that a volcano actually erupted during its mission. An eruption itself wasn't observed, but two images of the same region taken some time apart show a change in appearance of a volcano and nearby lava flows, suggesting that it had erupted at some point between the pictures being taken.

Venus' entire surface might have been reshaped in a massive event that took place between 300 million to 500 million years ago. During this time, it’s thought that volcanic eruptions covered the entire planet in fresh lava, wiping out much of its ancient history. This is why Venus has relatively few craters compared to planets like Mercury or Mars, whose surfaces are billions of years old.

The cause of this global resurfacing event remains a mystery. Scientists believe it may have been triggered by processes deep in Venus' mantle—the layer of molten rock beneath the surface that influences volcanic activity. Understanding what happened during this event is one of the key questions future missions hope to answer.

Getting a closer look at Venus' surface isn’t easy. The first missions to land on Venus were the Soviet Venera landers in the 1970s and 1980s. They survived only for a few minutes before being destroyed by the intense heat and pressure. However, they lasted long enough to be able to take images from Venus' surface. Venera 9, which landed on Venus on 22nd October 1975, took the first photo from Venus. In fact, it was the first photo from the surface of any planet other than Earth!

NASA’s Magellan mission, which orbited Venus between 1990 to 1994, used radar to map the planet from orbit, providing detailed images of nearly 98% of Venus’ surface. More recently, Venus Express, launched by the European Space Agency in 2006, studied the planet from orbit and gave scientists new clues about Venus' volcanic activity.

In the near future, there are plans for even more ambitious missions. Russia’s Venera-D, scheduled to launch after 2029, will attempt to land on the surface again and study Venus' geology up close. Other missions, like NASA’s DAVINCI and VERITAS, will study Venus from orbit, using radar and atmospheric probes to learn more about the planet’s volcanic history and potential past habitability.